Max Liljefors

Enter the Sensuous City

Humans are tuned for relationship. The eyes, the skin, the tongue, ears, and nostrils—all are gates where our body receives the nourishment of otherness.

David Abram

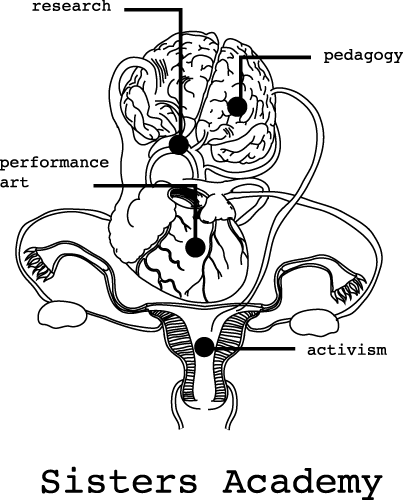

The Copenhagen-based performance group Sisters Hope fathoms the depth and breadth of the sensuous in their twenty-four-hour art performance Sensuous City, performed in July 2019 across various parts of Copenhagen.

It is a highly immersive work. Participants – a better term in this case than ‘the audience’ because it is impossible to take part in Sensuous City and remain a distanced observer – are gradually drawn into a state of keen and receptive experiencing, at the heart of which lies the question of the essence and value of the aesthetic.

The performance begins in the City Hall of Copenhagen, a richly decorated 19th-century building in the city centre, designed by architect Martin Nyrop and inaugurated in 1905. This is a highly significant starting point, as the building is the residence of the municipal council and the Lord Mayor of the Copenhagen Municipality. In short, it is the centre of urban politico–symbolic power. Into this centre of power – which is, at the same time, a symbol of the city as a community of citizens – the participants in Sensuous City are introduced by way of several thresholds. The first is the renunciation of sight: you are led blindfolded through the building’s labyrinthine interior, through corridors, across halls, up and down stairs, into underground chambers; spaces with their own atmospheres and echoes. During this process, you find yourself passing across still other thresholds, or perhaps better, through certain inner ‘mental membranes’. One is the awakening of your non-visual senses – hearing, touch, your proprioceptive awareness of your body’s position and direction. Another is the silent bonding with unknown others. As the performance guides direct your progression forward with gentle touches, and as they tenderly wash your hands in the dark, and as you sense the wordless presence of other participants, the very perception of yourself as a clearly outlined ‘I’ is slightly blurred. You find yourself enveloped in the silent kindness of strangers.

The hours spent in the City Hall serve as a ritualistic yet playful primer for the wider explorations that follow. One more aspect deserves to be highlighted, though. The entire performance – and I realize in hindsight some fifty to eighty participants divided into smaller groups must have been manoeuvred simultaneously through the building – occurs during a typical working day at the City Hall. Hence, staff members rush by engaging in various tasks and conversations, but seemingly oblivious (perhaps by instruction) of the artistic endeavour that unfolds in their midst. Thus, two universes – one guided by rational efficiency and one dark and glowing with sensuous receptivity – flow through each other, yet never mix.

The doors to the city open.

Participants are led in groups into the urban environment, no longer blindfolded but subjected to other, smoother manipulations of their sensory apparatuses. I refrain from describing the details, but the elemental act of walking constitutes the core of this part of the performance. As participants move through the urban ambience, simple yet delicate adjustments of the conditions of sensing create multilayered, constantly shifting experiences. In this way, sensory impressions are orchestrated through fundamental means, such as prolonged duration and a slowed-down pace. Aspects of the city that tend to pass unnoticed – the presence of useless objects, sunlight that reflects in foliage, voices, sounds and winds that fill the space between the facades, how surfaces of varying texture feel against your fingertips, your body’s understanding of distances; this and more rise to awareness, and thus, awareness is sharpened, becomes more receptive.

The performance unfolds amongst the hustle and bustle of city life but is never engulfed by it. Again, two universes sail through each other without dissolving into one another. In hindsight, I picture, as from above, the groups of participants that slowly advance through the city as forming meandering corridors of perceptual intensity inside the everyday urban commotion, drilling into a secret fabric concealed beneath the commercially driven, forward-looking, never present-minded running to and fro of contemporary city dwellers. The performance mines the city for a hidden resource, abundant yet scarcely harvested: non-instrumental sensuousness and presence.

After several hours, the performance participants eventually reach – on different, winding paths – what is difficult not to regard as the very opposite of the City Hall in the force field that constitutes the city: Sisters Hope’s headquarters, located in a worn-down industrial area in the outskirts of the city centre. If the former is the centre of politico-symbolic power in the city, the latter forms its poetico-sensuous counterpart. In a spacious hall, elegantly yet modestly furnished, participants, still attuned to aesthetic receptivity, are invited to share the elemental tasks of human life: eating, doing the dishes, playing, sharing experiences from the day, sleeping – interspersed by ‘activities’ that further explore the depths of sensuous awareness. Again, I refrain from a detailed account, but what comes forth as the primary component in this phase of the performance is the phenomenon of gathering. No longer tied to the smaller choreographed groups, the individual participants enter into a larger, looser community with a broader range of choices and relations.

What is Sensuous City about?

Several things. There is the actualization of the dimension of the sensuous, which stretches from sensory stimuli to interpersonal sensuality. There is the (re-)discovery of what Sisters Hope refers to as ‘the Poetic Self’, which I understand to mean a universal human potential for fearless creativity and responsivity. And there is the plea for, and claim to, the city as a space for non-instrumental, non-commercial sensuous exploring.

For this participant and reviewer, however, the most radical aspect of Sensuous City is the connection that is revealed between the sensuous and the collective, in ways that range from sharing, bonding, and trust between individuals, to the organization and governing of larger groups. For instance, walking silently together over a prolonged time, for the purpose of sharing an open-ended experience of the city, is not merely to cover a geographical distance together but to attune oneself, corporeally as well as mentally, to each other’s pace, rhythm, perceptual foci, and hesitancies.

The central role of walking in the performance relates it to the Situationist practice of dérive, a kind of walking through an urban milieu with heightened awareness to study what Guy Debord called the city’s ‘psychogeography’. Sensuous City shares the political criticality inherent in such practices when employed in the context of late modern urbanity, where access to spaces is regulated by political and commercial powers that shape and delimit our sensuous grasp of what the city is.

But to this critique, Sisters Hope adds a dimension of community-building based on mutual responsivity and responsibility, which has a different but no less crucial political relevance. The city today is de facto shared by individuals and groups of different geographical, ethnic and religious backgrounds, different histories and sometimes conflicting political and ideological dogma. Dogma invariably divides, but experience, as a profound, reflected way of relating intensely to the world through the senses, has the potential to bridge such divisions – that is, if the testimony of experience is shared and received.

Why? Because aesthetic awareness harbours within itself a component of what British philosopher Iris Murdoch has named ‘unselfing’. Before a demanding work of art, Murdoch writes,

the walls of the ego fall, the noisy ego is silenced, we are freed from possessive selfish desires and anxieties and are one with what we contemplate, enjoying a unique unity with something which is itself unique. (Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals, 59)

Through the aesthetic, then, we can learn to see what is before us more clearly, grasp the world more justly. Or, as elaborated by German philosopher Martin Seel, to comport ourselves aesthetically vis-à-vis the world requires us to lose ourselves to a certain extent. This, in turn, brings about a new freedom for us to recalibrate our trust and distrust in the world and in ourselves. In this way, dogma, as products of the intellect, draw up borders and demarcations, while aesthetic awareness insists on the possibility of opening up and penetrating those borders that divide the I from the Other. This the reason why, in the history of philosophy, the human ability to perceive beauty has so often been linked to the capacity to love as well as to observe ethical self-restraint.

On the second day of the performance, the participants in Sensuous City return to the City Hall, bringing with them found objects and written reflections as tokens of their experiences and of their willingness to share them. These objects and notes are then exhibited in glass vitrines in the public parts of the building. Only at that point do the two universes – the politico-symbolic and the poetic-sensuous – really meet, as the latter lays claim to a place and value in the heart of the former. The fact that the displayed objects may seem useless – a paled photograph found in a trashcan, a piece of cardboard rescued from the gutter, or a fallen leaf picked up beneath a park bench – does not mean that the encounter is marginal. On the contrary, the very poverty of those treasures articulates a vision of another society, more alive to the poetic and the sensuous, where shared experiences rather than contractual obligations form the fabric of community.